Marriage, Polygamy, and the Provo Insane Asylum

Over the next couple of weeks, I want to highlight some of my current research. The first is a collaborative transcription project focused on the colonization of the Big Horn Basin in Wyoming. Last semester, a graduate research student transcribed all the correspondence in Abraham Owen Woodruff Collection at Brigham Young University. Although the correspondence focuses on the community’s irrigation projects, there are snippets that help researchers to understand how religious faith and sexuality functioned in the community.

One of these is a non-tithe payers list submitted to Woodruff in the early 1900s. When I saw these lists, I realized they were an opportunity to explore the reasons people stopped attending church in the nineteenth century. I asked another research assistant to create files for the men named on Google Drive and to upload relevant material from the Church History catalog and FamilySearch.

I won’t share each of the men’s stories because we will probably publish an article based on this research on how scholars should define religious faith and church discipline. I do, however, want to highlight one story we have found–that of Albert Henry Dickson.[*] As you will see, Dickson’s life story also raises questions about marriage, how we read sources, and the silence of the archives.

Dickson is not well-known in Mormon history. He did not hold influential positions in the Church, nor is he mentioned in local histories. He was born in 1862 to Stuart and Mary Jane Dickson. Stewart worked as a mill hand in Morgan, Utah.

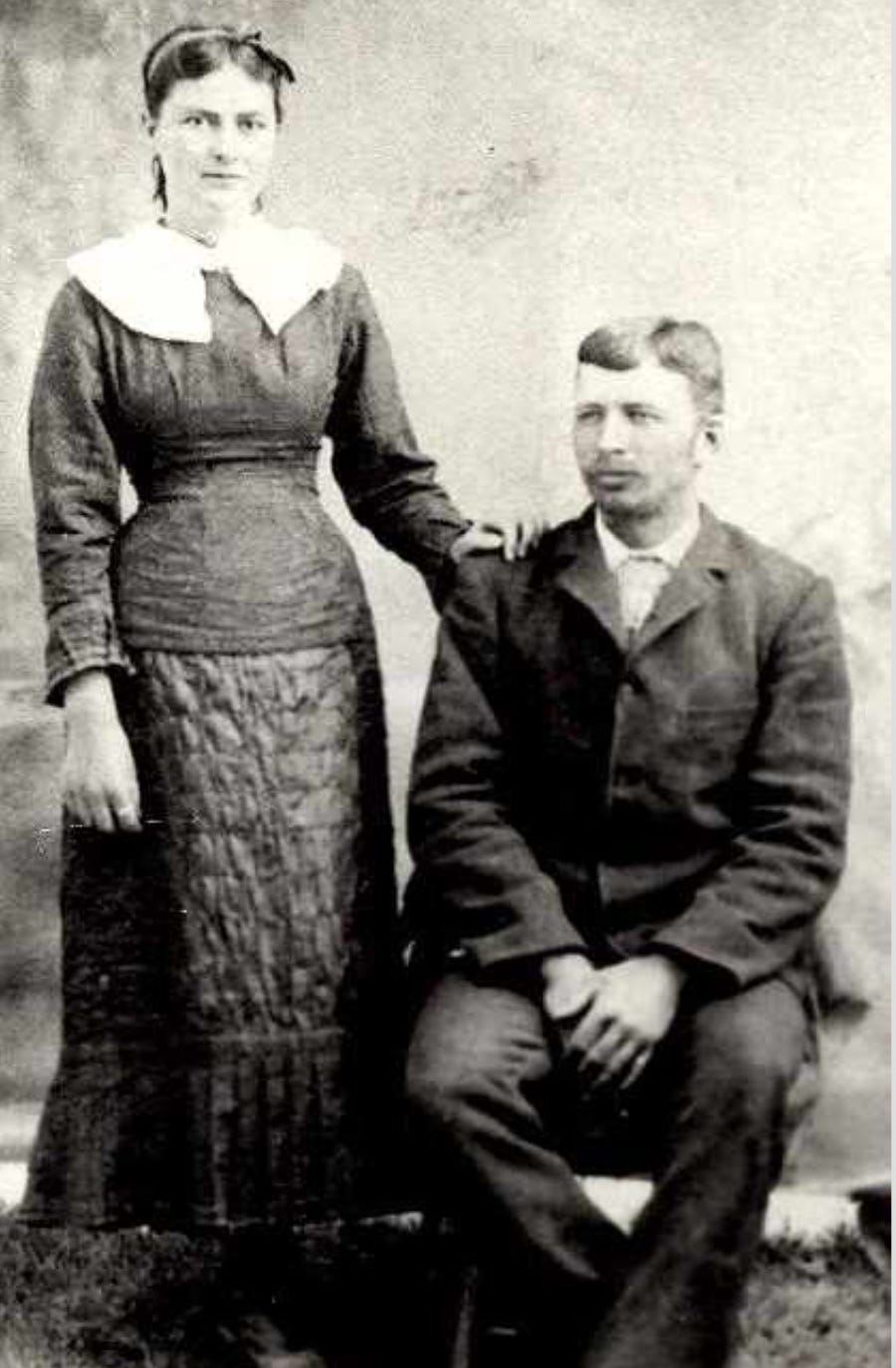

The family eventually moved to Woodruff, Utah, a small farming community near Bear Lake. There, he married Julia Inzie Eastman in 1885.

In 1886, Julia gave birth to a daughter named Eulalia.

A son followed two years later, but he only lived for a few months. Family histories suggest Julia struggled with his death, becoming “morose” and even violent. The record is unclear on this point, but Albert may have divorced her in response. Eulalia lived for a time with her grandmother, and local newspapers contain a few references to a court case between the two in the 1890s.

I could not locate the court case to determine whether it is a record of their divorce. It’s also possible it was a dispute over the mental health care Julia should receive. According to family histories, the Wyoming State Insane Asylum briefly committed Julia in 1890 or 1891 and released her 3 months later. The asylum reported that she “was in good physical condition and [had] improved.” It is possible that Julia or her family disagreed with her incarceration.

On December 18, 1893, Albert married a seventeen-year-old girl named Ellen Bryson. Julia became depressed, and one of her uncles “arrested” her, committing her to the Provo Insane Asylum. A month later, Ellen and Albert were sealed for time and all eternity in the Salt Lake City temple.

When Milton Hardy went to Provo in June 1900 to record the names of the women living at the insane asylum, he listed her as single, suggesting that if her husband rarely visited, if they were still married.

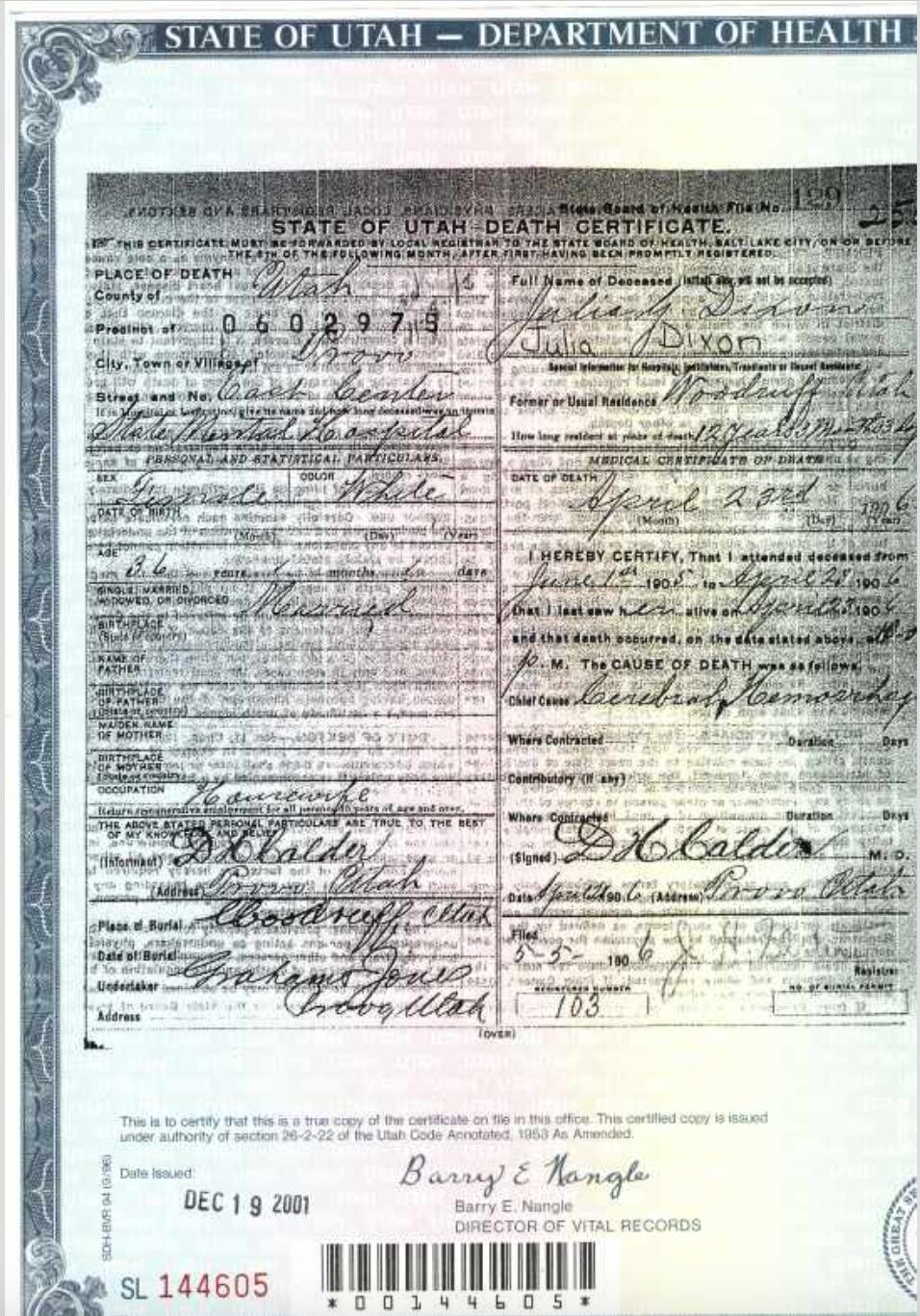

After her death six years later from a cerebral hemorrhage, the asylum sent her remains to her brother, not her husband, for burial. Against this evidence stands Julia’s death certificate. On her 1906 death certificate, the coroner lists her as a married woman.

The timing of these events raises questions about Julia and Albert’s relationship. Did Albert and Julia officially divorce? Are the newspaper references to a court case between Julia and Albert Dickson a divorce record? A suit for abandonment? Why did Albert wait until Julia was in an insane asylum to seal himself to Ellen? Did he worry that the church would not recognize his divorce? Did he worry that the church would require Julia's consent as his first wife to any subsequent marriages? Did he consider himself still married to Julia? Why did the coroner list Julia as a married woman?

At the heart of these queries is another: How do we define marriage and polygamy? If Julia and Albert were still married in December 1893, Albert took part in post-manifesto polygamy without question. A civil divorce would not undermine this interpretation. Albert’s faith would have recognized both of his marriages, even if the territorial government did not. FamilySearch records his sealings to both wives — Julia in 1886 and Ellen in 1894. Civil divorces did not dissolve those ties, and family histories suggest Julia considered herself his wife for years after their possible divorce. The belief that marriages continue into the eternities also meant that Julia would be a polygamous wife in the afterlife, even if she didn’t consider herself one in this one.

I also wonder if Albert’s tumultuous marriage is why the church listed him as a non-tithe payer. The bishop did not provide a reason Albert was not paying his tithe. It’s possible that he lost faith in the church as he navigated the loss of a child and his wife’s resulting depression. He may have divorced his wife soon after seeing their son’s death, or perhaps he waited several years, hoping that she would heal. He may have also still felt that she was his, despite their civil divorce. Ultimately, their life story highlights how little we know about the past. Although there’s a lot of historical evidence for the lives of individuals like Joseph Smith, Parley P. Pratt, and Brigham Young, we know vanishingly little about the lives of working-class men and women. We can summarize what we know about Albert and Julia Dickson in a little more than a thousand words.

[*] We think it is likely that Albert Henry Dickson is the person listed on the non-tithe payers list. Although his cousin lived nearby and shared the same name as his cousin, he was a local bishop and was not a member of the same ward.